The inflation blame game

8 min. read •

One day, I was at the mall looking for a new pair of jeans. After trying a few on, I made my way to the cash register. When it was time for the guy in front of me to pay, he pulled out a money clip with a stack of dollar bills thicker than the folded pair of jeans I had picked out. I'm not sure if he was trying to impress me, the cashier, or his friends, but he slowly pulled out five $100 bills, one by one. Unfortunately for him, his dollar bills couldn't impress me, because shopping for clothes makes me hungry. I was too busy thinking about the delicious, golden Hot Dog on a Stick that would soon be in front of me. The cashier took the $100 bills and, after inspecting them for about 2 seconds, she said, “Sorry, I can't accept these. They are counterfeit."

Now the situation had my undivided attention, and made me wish I had some popcorn. "What!? Are you kidding me!?" he said. "I just got this money from the ATM. Look how crisp it is." She replied, "I'm sorry, there's nothing I can do." He snatched one of the $100 bills back and gave her another one. She inspected it and once again stated it was counterfeit. This process continued, with the guy getting more upset and me getting hungrier. It went on for so long that I put down the pair of jeans and walked to the food court.

I don't know what the resolution was to that situation, but it did get me thinking while I dunked my long-awaited corn dog into ketchup and mustard, and back to the ketchup again. Assuming there was no mistake on the cashier's part, and the dollar bills were counterfeit, what would have happened if the cashier had unknowingly accepted them? The man would have left the store happily with his merchandise, knowing he had the crispiest dollar bills in the land. The money would have eventually been taken to the department store's bank, and once the bank received the money, it would almost certainly detect that it was counterfeit. Instead of depositing it into the department store's bank account, the money would be confiscated, sent to the Secret Service, and they would investigate from there.

Ultimately, the merchandise the man left the store with would have been unpaid for. From the perspective of the department store, it would have been equivalent to someone shoplifting the same merchandise. In the U.S., you can go to prison for counterfeiting money (U.S. dollar bills) and destroying money, but what if the government did not care who created money and how much of it was in circulation? It would not be long before $100 bills were like pennies, lying in the street, and not worth most people's time to pick them up.

It's important to understand that money is not what makes someone wealthy. That statement may sound odd, but who is better off - a man with $2 million stuck in the desert alone with no chance of being found, or a person with no money in the middle of a city? The man in the city is more well off, because there is always the chance that a friend or good Samaritan may help him, or he may find work or shelter, or as a last resort, he has the option to steal. The man in the desert has nothing to buy with all his money.

Money simply allows people to store value so that they can exchange it for something else in the future. Therefore, it is vital that the next person you want to buy something from has the confidence that they can buy something else in the future with the money you gave them today. Just as importantly, people should expect that $50 given to them on one day will buy them about the same number of things the next day, week, month, etc. If they don’t have that expectation, they may ask you for more money now to account for uncertainty and inflation later. Crisp or not, if your dollar bills don't hold their value into the future, they're useless.

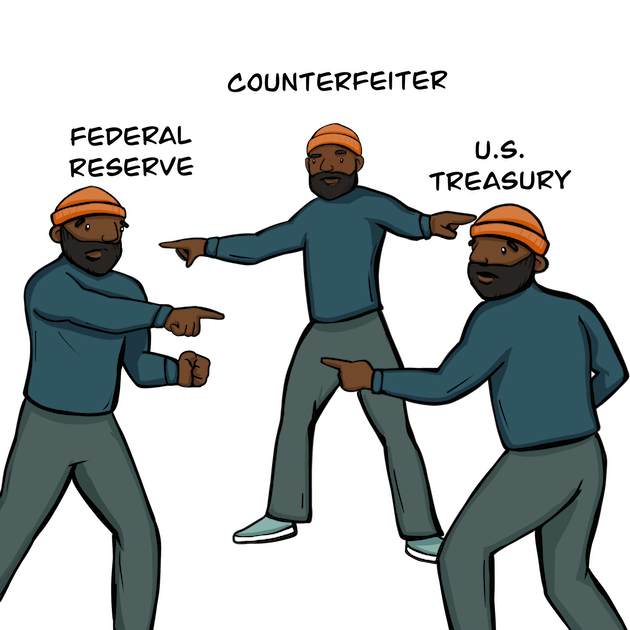

We may have not reached the point where $100 bills are like pennies, but a large amount of money is being created out of thin air. Not by counterfeiters, but by the central bank of the United States, the Federal Reserve. If your neighbor decided to counterfeit money, but hid all that money under their bed and never used it or mentioned it to anyone, then it would never have an impact on the economy or have a chance to devalue everyone else’s hard-earned dollars. The Federal Reserve, on the other hand, creates money legally with the stroke of a keyboard, but as long as they don't let it escape into the economy, it has almost the same effect as the counterfeit dollars under your neighbor's bed - very little.

You may remember that during the pandemic, the government sent out stimulus checks, unemployment benefits, and payroll protection loans to businesses (most of which were forgiven and did not have to be paid back). Where did the government get the money it gave everyone? The Federal Reserve cannot directly lend money to the government, but the government can borrow money from banks, corporations, other governments, and individuals. It does this by issuing U.S. Treasury bonds, something it’s done since the First World War. Since the government borrowing money from one person and lending it to someone else doesn't create money out of thin air, what does it have to do with inflation? Great question! The answer involves the Federal Reserve doing something unusual, something it did not start doing until recently. The Federal Reserve started buying enormous amounts of bonds from others who had previously bought them directly from the government. However, it buys these bonds with the money it creates out of thin air.

This next example is an oversimplification, but it shows how government spending and money creation by the Federal Reserve can contribute to inflation. (One important note is that when I refer to the U.S. Government in this example, I mean specifically the U.S. Treasury, which is separate from the Federal Reserve.) Suppose there is a guy named Peter with an extra $1,200 sitting in his bank account that he wants to invest. The United States government reminds Peter that he can always lend his money to it, with the promise that it will be paid back in full several years from now, with interest along the way. Peter likes the idea and lets the government borrow $1,200. The government gives Peter a bond in exchange, which is the promise of the government that they will pay him back, plus interest, in a specific span of time. The government then takes that $1,200 and gives it to another guy named Paul in a stimulus check. A couple of weeks go by, and Peter sees something on eBay that he wants, but doesn't have money for. Instead of waiting to get paid back by the government, he puts his bond up for sale, and someone else buys it. Little does Peter know, the buyer was the Federal Reserve, and they paid for it with money they created out of thin air. Honestly, Peter couldn't care less about this, because as long as the Federal Reserve makes the money, it’s not considered counterfeit. Peter uses his money to attempt to buy a computer on eBay, but he loses and is outbid by (surprise, surprise) Paul.

To recap, originally Peter had $1,200 and Paul had $0. After the Federal Reserve came in, Paul and Peter have $2,400 combined. Like magic, an extra $1,200 was created out of nowhere when the Federal Reserve bought Peter's bond! Since this extra money appeared out of thin air, once it entered the economy, it effectively devalued all the existing money everyone else had worked to earn. In the end, the whole process has similar results to counterfeiting. The difference is that instead of a store being robbed of its merchandise through counterfeit bills, the value of everyone's money is taken away.

Not every dollar created by the Federal Reserve contributes to inflation, like in the example I gave. The owner of the debt before the Federal Reserve buys it could be various individuals and institutions (e.g. banks, insurance companies, hedge funds, pension funds, mutual funds and more). Each outcome can differ depending on who receives the money created by the Federal Reserve. Most banks have a special relationship with the Federal Reserve, and because of how they operate, their impact on the economy can differ when they receive newly created money from the Federal Reserve. It is also not guaranteed that the person or institution that receives this new money will spend it. However, during the present time with a decrease and delays in production, people's savings plummeting below pre-pandemic levels, and U.S. credit card debt at an all time high, the combined actions of the Federal Reserve and government are almost certainly a strong contributor to high inflation.

You may be thinking:

Why is the government allowing this to happen?

Most people forget that nothing the government offers is free. Things like "free healthcare" and "free education" are dishonestly named, because you and other Americans pay for them in taxes and/or inflation. Politicians know that one of the best ways to get elected is by promising 'free' stuff, but they have to figure out how to pay for it. They know that taxing is extremely unpopular (and can lose them an election). Even if they managed to get citizens to give 50% of their paycheck as taxes, that would not be nearly enough to pay for what they want to spend and what the government has already promised to spend. So the government borrows money from all kinds of people, companies, and other governments instead. When it is time to pay back the debt, the government can do so by taxing citizens, or by borrowing the money again. Since 2009, the Federal Reserve has intermittently and indirectly become one of the largest buyers of debt from the government. They have called this new practice 'Quantitative Easing'. The Federal Reserve believes that doing this will inject more money into the economy, and will make people buy more things and invest, which causes companies to create more goods and services while hiring more people. Overall, they think it will help the economy grow. However, it can have other effects, like creating asset bubbles (e.g. record breaking home prices), making it easier for the government to keep borrowing without its citizens being aware, and encouraging individuals and institutions to take on more risk when investing. When quantitative easing accompanies mass government spending, this combo contributes to the high inflation we are seeing right now.